1. The Architecture of Sovereign Fraud

The release of the Paradise Papers in November 2017 was a landmark moment for the global understanding of offshore financial secrecy. These documents provided a rare look into the internal operations of the "Magic Circle" of offshore law firms. While the earlier Panama Papers focused on the mass production of simple shell companies, the Paradise Papers revealed a more sophisticated level of financial engineering. This collection of 13.4 million documents from Appleby and Asiaciti Trust showed how multinational corporations and political figures use bespoke structures to hide asset ownership and avoid regulatory oversight [1].

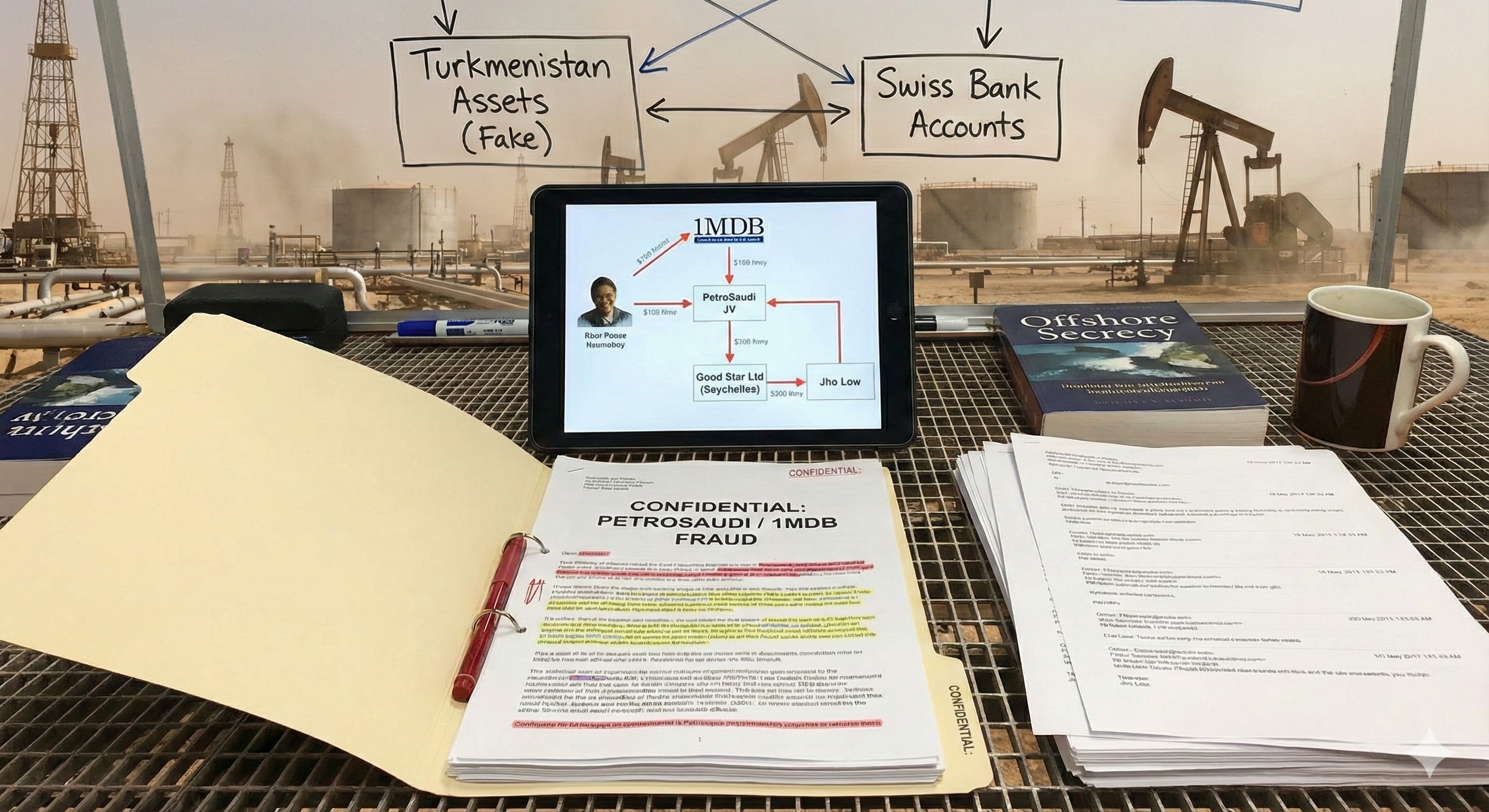

Within this data, the records involving PetroSaudi International serve as a definitive case study in the creation of fake value. Analyzing the PetroSaudi oil data requires a forensic look at the corporate and legal structures that allowed nonexistent or contingent assets to be valued at billions of dollars. The scandal involving 1MDB and PetroSaudi is not just a story of theft. It is a demonstration of how the global financial infrastructure was weaponized to turn a worthless asset in the Caspian Sea into a 1 billion dollar cash injection from the Malaysian public [3].

This report combines the revelations from the Paradise Papers with evidence from U.S. Department of Justice forfeiture complaints and whistleblower leaks. It examines the two specific phases of the PetroSaudi fraud. First, it looks at the fabricated valuation of the Serdar oil field in Turkmenistan. Second, it follows the subsequent money laundering operations involving deep water drillships in Venezuela. By connecting these disparate points, the analysis reveals a systemic failure of compliance and the deliberate use of sovereign immunity to protect illegal capital flows [5].

1.1 The Nature of the Paradise Papers Leak

The Paradise Papers leak offers a distinct advantage over other financial disclosures due to the "unstructured" nature of a significant portion of the data. Unlike structured corporate registries that merely list directors and shareholders, the Appleby files contain internal emails, compliance checklists, risk assessments, and draft contracts.[7] These documents provide the "mens rea" or intent behind the corporate structures.

For PetroSaudi, the Appleby files serve as the "corporate memory" of the fraud. They document the internal discord within the law firm regarding the client's high risk profile, the scramble to justify valuations after funds had already been transferred, and the intricate layering of shell companies in the Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands (BVI), and Barbados designed to distance the perpetrators from the proceeds of the crime.[8] The leak confirms that the offshore service providers possessed information that contradicted the public narratives presented to the 1MDB board and Malaysian regulators, yet continued to facilitate the transactions under the guise of legal privilege and client confidentiality.[1]

2. The Appleby Connection: Compliance Failures and "Code Red"

The role of Appleby, a firm that prided itself on being a tier one offshore legal advisor, is central to understanding how PetroSaudi maintained its veneer of legitimacy. The Paradise Papers reveal that Appleby was not merely a passive administrator but an active gatekeeper that repeatedly overrode its own internal controls to service the PetroSaudi account.

2.1 The Compliance Void and PEP Risk

The leaked documents highlight a systemic failure within Appleby to adhere to Anti Money Laundering (AML) and Know Your Customer (KYC) regulations, particularly regarding Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs). Tarek Obaid, the co founder of PetroSaudi, was a known PEP with direct links to the Saudi royal family and high level Malaysian officials.[10] Under standard AML protocols, such a client requires Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD) to establish the source of wealth and funds.

However, the Paradise Papers indicate that Appleby frequently lacked basic information on the beneficial ownership of entities within the PetroSaudi network.

- The BMA Audit: In 2013, the Bermuda Monetary Authority (BMA) conducted an on site audit of Appleby’s Bermuda office. The audit found significant deficiencies, noting that the firm had "no evidence" that it identified risks of money laundering and terrorism financing for many clients.

- The Secret Fine: A confidential document from October 2015, found within the leak, revealed that Appleby’s Bermuda office had "settled" a fine imposed by the BMA. The firm set aside US$500,000 for this fine, but the existence of the penalty and the specific compliance failures were kept "entirely private" by the regulators. The BMA agreed to "no public censure," allowing Appleby to maintain its reputation while harboring high risk clients like PetroSaudi.[8]

2.2 Internal Dissent and the "Code Red"

The internal culture at Appleby regarding the PetroSaudi account was characterized by tension between compliance officers and fee earning partners. The leak reveals that as the 1MDB scandal began to surface in the media, driven by the initial whistleblower disclosures from Xavier Justo in 2015, Appleby personnel scrambled to assess their exposure.

- The Justo Context: While Xavier Justo, a former PetroSaudi director, provided the operational emails proving the theft, the Paradise Papers provided the corporate context. Justo’s arrest in Thailand and the subsequent forced confession were orchestrated to suppress the very data that Appleby held in its archives.[11][12][13]

- Risk Assessments: Internal emails show Appleby employees flagging the PetroSaudi entities as high risk. The firm’s "Compliance Group" raised queries about the origin of the billions flowing through the accounts, specifically the US$1 billion injection from 1MDB. These queries were often met with incomplete answers or pressure from partners to expedite the transactions to satisfy the client’s urgent timelines.[8]

This environment of "willful blindness" allowed PetroSaudi to utilize Appleby’s trusted reputation to interact with major global banks. The firm’s imprimatur was essential for opening accounts at institutions like JP Morgan and RBS Coutts, which might otherwise have rejected a newly formed entity with no operational track record and vague asset valuations.[5]

3. The Turkmenistan "Oil Data": Anatomy of a Fabrication

The central query regarding "PetroSaudi Oil data" centers on the asset used to justify the initial joint venture (JV) with 1MDB. The premise of the deal was a classic resource for capital swap: 1MDB would provide US$1 billion in cash, and PetroSaudi would provide oil assets valued at US$2.7 billion. The Paradise Papers, supported by DOJ filings, prove that the "oil data" supporting this valuation was fundamentally fraudulent.

3.1 The Serdar Field and the "Farm In" Agreement

The primary asset claimed by PetroSaudi was an interest in the Serdar Oil Field (also known as Block III) in the Caspian Sea. This field is located in a disputed maritime zone claimed by both Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan, a geopolitical reality that rendered any development rights highly speculative and risky.[14]

The Paradise Papers reveal the tenuous nature of PetroSaudi’s claim to this asset:

- Lack of Ownership: PetroSaudi did not own the field. Instead, on July 4, 2009, PetroSaudi signed a "farm in" agreement with Buried Hill Energy, a Cyprus based energy company that held a Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) with the Turkmenistan government.[14]

- Conditions Precedent: The farm in agreement stipulated that PetroSaudi would only acquire a 50% working interest in the PSA if it funded all appraisal and pre development costs.

- Termination: Crucially, PetroSaudi never fulfilled these funding obligations. The Paradise Papers indicate that the farm in agreement was terminated shortly after the JV with 1MDB was finalized. Consequently, at the time the funds were transferred, PetroSaudi’s actual possessory interest in the Serdar field was legally negligible, if not non existent.[14]

3.2 The Edward Morse Valuation Report

To bridge the gap between the "zero" actual value of the asset and the US$2.7 billion required to carry the fraud, PetroSaudi engaged Edward Morse, an American banker and energy sector expert. The internal correspondence regarding this valuation is among the most incriminating data in the leak.

- The "Zero" Internal Rating: Just weeks before the deal was consummated, Tarek Obaid had internally assessed the value of the Turkmenistan project as "zero" due to the territorial dispute and the contingent nature of the contract.[4]

- Guided Valuation: The leaked emails show Patrick Mahony, a PetroSaudi director, explicitly guiding Morse toward the desired figure. In a correspondence dated shortly before the deal closing, Mahony wrote to Morse: "We are looking for a mid range of $2.5b." Morse’s reply was succinct: "OK got it!".[4]

- Timing of the Report: 1MDB’s CEO, Shahrol Halmi, signed the engagement letter for Morse on September 29, 2009 the exact day the funds were being transferred to the JV. This chronology proves that the valuation was a "post facto" window dressing exercise intended to create a paper trail for a decision that had already been made. The valuation report was not a basis for investment due diligence; it was a compliance artifact created to deceive the 1MDB board and auditors.[3]

3.3 The Disconnect in Geological Data

The "oil data" provided to Morse for the valuation was supplied entirely by PetroSaudi. There is no evidence in the Paradise Papers that Morse conducted independent geological surveys or verified the reserve estimates with the Turkmenistan government. The valuation relied on the "Resource Based" method, which projects future cash flows from unproven reserves. By manipulating the inputs, specifically the estimated recoverable reserves and the probability of commercial success, the valuation was inflated to the required US$2.9 billion figure (which exceeded the $2.7 billion requirement, providing a "buffer").[4]

The reality of the asset was starkly different. Buried Hill, the actual license holder, had struggled for years to develop the field due to the sovereignty dispute. The "farm in" was essentially an option to spend money, not an asset with book value. Yet, through the alchemy of the Morse report and Appleby’s corporate structuring, this liability was transformed into the cornerstone of a multi billion dollar sovereign wealth partnership.[14]

3.4 The Asset Swap and Erasure

The fraud did not end with the valuation. Six months after the JV was formed, in March 2010, the "oil assets" were disposed of.

- The Swap: 1MDB sold its 40% equity stake in the JV back to PetroSaudi.

- The Consideration: Instead of cash, 1MDB received Murabahah Notes (Islamic debt paper) with a face value of US$1.2 billion.

- The Result: This transaction effectively removed the non existent oil assets from the books. 1MDB was left holding debt paper guaranteed by PetroSaudi a company with no substantial assets other than the stolen cash itself. The farm in agreement with Buried Hill was formally terminated, erasing the original "asset" from the equation entirely.[3]

4. The "Good Star" Diversion: Unveiling the Theft Mechanism

While the fabricated oil data provided the cover, the actual theft was executed through banking transfers that relied on obfuscating the beneficial ownership of the recipient accounts. The Paradise Papers provided critical evidence that dismantled the "loan repayment" narrative used to explain the initial diversion of funds.

4.1 The Bearer Share Revelation

- US$300 million went to the legitimate JV account.

- US$700 million was diverted to an account at RBS Coutts in Zurich held by Good Star Limited.[3]

PetroSaudi and 1MDB officials claimed that Good Star was a wholly owned subsidiary of PetroSaudi, and the US$700 million was a repayment of a loan that the parent company had advanced to the JV. However, the Paradise Papers and banking records confirmed that Good Star was a Seychelles registered company with bearer shares.[15]

- Jho Low’s Ownership: The leak revealed that the single bearer share of Good Star was held by Low Taek Jho (Jho Low). This irrefutably proved that Good Star was not a subsidiary of PetroSaudi but a personal vehicle for Jho Low.[16]

- Banker Complicity: When Deutsche Bank (Malaysia) raised questions about the beneficiary of the US$700 million transfer, 1MDB management provided false confirmations. The Paradise Papers show that the offshore corporate structure was designed to make verification of Good Star’s ownership nearly impossible for compliance officers in real time, as the Seychelles registry did not publicly disclose bearer share owners.[15]

4.2 The Role of "Prince Group" and Other Actors

The Paradise Papers also contextualize the PetroSaudi fraud within a broader ecosystem of illicit finance. The data links Appleby’s lax compliance to other notorious figures, such as the Prince Group, a Cambodian conglomerate implicated in money laundering, and Glencore’s dealings in the Democratic Republic of Congo.[17]

This comparative context is vital. It demonstrates that the failure to detect the Good Star diversion was not an isolated error but part of a business model where high fees incentivized the bypassing of "Know Your Customer" (KYC) rules. Just as Appleby facilitated Glencore’s loans to sanctioned individuals, it facilitated the structures that allowed Tarek Obaid and Jho Low to move 1MDB funds through the global banking system undetected.[16]

5. The Venezuelan Pivot: PetroSaudi Oil Services (Venezuela) Ltd

Following the initial theft in 2009 2010, the conspirators needed a mechanism to launder the proceeds and create the appearance of legitimate business activity. This led to the second phase of the fraud involving PetroSaudi Oil Services (Venezuela) Ltd (PSOSL) and deep water drilling contracts in Venezuela. The Paradise Papers provide extensive details on this Barbados based entity.[10]

5.1 Incorporation and the Drillships

- The Assets: The entity purchased two drillships, the PetroSaudi Saturn and the PetroSaudi Neptune.[20]

- The Contract: PSOSL entered into a drilling contract with Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) for the Mariscal Sucre offshore natural gas project.[21]

The choice of Barbados for PSOSL was strategic. The Paradise Papers show that Barbados offers a network of Double Taxation Treaties (DTTs) and corporate secrecy provisions that are advantageous for holding companies conducting business in South America.[10] The directors of PSOSL, as revealed in the leak, included Tarek Obaid and other PSI operatives, with corporate secretarial services provided by Lex Caribbean.[10]

5.2 The "Pay Now, Argue Later" Clause and Arbitration

The drilling operation in Venezuela became the subject of a massive arbitration dispute that the conspirators used to legitimize the flow of funds.

- The Dispute: In 2015, PDVSA ceased payments to PSOSL, citing non performance. PSOSL initiated arbitration under UNCITRAL rules in Paris.

- The Contract Mechanism: The drilling contract contained a highly favorable "pay now, argue later" clause. This stipulated that PDVSA was obligated to pay invoices immediately unless they were formally disputed within 15 days. Additionally, the contract was secured by a Standby Letter of Credit (SBLC) issued by Novo Banco.[22]

- The Award: The arbitration tribunal ruled in favor of PSOSL, ordering PDVSA to deposit US$500 million into an escrow account to cover unpaid invoices. This account was managed by the UK law firm Clyde & Co.[23]

This arbitration award effectively "washed" the funds. The revenue generated by the drillships, which were purchased with stolen money, was now converted into a legal judgment from an international tribunal, giving it a veneer of legitimacy that could withstand banking scrutiny.

5.3 The DOJ Intervention and Sovereign Immunity Defense

The U.S. DOJ disrupted this laundering cycle by filing a civil forfeiture complaint against the funds held in the Clyde & Co escrow account.

- The Legal Theory: The DOJ argued that because the drillships were purchased with misappropriated 1MDB funds, any revenue they generated (including the arbitration award) represented the "proceeds of crime".[24]

- Sovereign Immunity Argument: PetroSaudi attempted to block the forfeiture by arguing that the funds were protected under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA). They claimed that because the funds originated from PDVSA (a Venezuelan state entity) and involved 1MDB (a Malaysian state entity), the U.S. courts had no jurisdiction to seize them.[6]

- The Ruling: The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit rejected this defense. The court ruled that PSOSL was a private entity, not a sovereign one, and that the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act did not protect private property derived from criminal activity, even if the victim or the counterparty was a state actor. The court affirmed the DOJ’s right to seize the US$330 million remaining in the UK escrow account.[6]

6. Broader Economic Implications: "Sand the Wheels" in ASEAN

The PetroSaudi scandal provides compelling empirical evidence for the "Sand the Wheels" hypothesis in development economics, which posits that corruption hinders economic growth by misallocating resources and increasing uncertainty. The findings from the research material allow for a detailed analysis of how this specific case impacted the ASEAN region.

6.1 The Cost of Corruption in Malaysia

The 1MDB scandal, facilitated by the PetroSaudi fraud, saddled Malaysia with an estimated US$7.8 billion in debt.[25]

- Opportunity Cost: The billions diverted to Jho Low’s luxury spending (yachts, art, gambling) and Tarek Obaid’s personal accounts represented a direct loss of development capital. Funds intended for energy security (the original pretext of the Turkmenistan JV) and infrastructure were removed from the Malaysian economy.[26]

- GDP Impact: World Bank estimates suggest that corruption can cost a country up to 5% of its GDP annually. For Malaysia, the reputational damage resulted in a "trust deficit," deterring Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and increasing the cost of borrowing for the state.[27]

6.2 Transmission Channels of Economic Damage

The research highlights three primary transmission channels through which the PetroSaudi corruption damaged the Malaysian economy:

- Investment Channel: The "white elephant" nature of the investment, paying for non existent oil fields, meant that public investment had a negative multiplier effect. Instead of generating jobs or energy, the capital was exported to Switzerland and the Caribbean.[28]

- Human Capital Channel: The diversion of state resources forces cuts in other sectors, such as education and health. The long term impact is a degradation of human capital, which is a primary driver of sustainable growth.[30]

- Institutional Channel: The scandal compromised key institutions, including the Attorney General’s Chambers and the Malaysian Anti Corruption Commission (MACC), which were initially blocked from investigating the fraud. Restoring institutional integrity is a generational challenge.[32]

6.3 Anti-Corruption Strategies - Singapore vs. Malaysia

The fallout from 1MDB highlighted the divergence in anti corruption strategies within ASEAN.

- Singapore: Adopted a rigorous enforcement approach. The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) shut down the local branches of BSI Bank and Falcon Bank for their role in facilitating 1MDB transfers. Singapore’s use of digital forensics and its "zero tolerance" policy have kept it ranked as the least corrupt nation in Asia (CPI Rank 3 globally).[34]

- Malaysia: While Malaysia has introduced the National Anti Corruption Plan (NACP) 2019 2023 to address the systemic weaknesses exposed by 1MDB, the implementation has been uneven. The NACP focuses on procurement reform and asset declaration, but the political instability following the scandal has hampered consistent enforcement compared to its southern neighbor.[32]

7. Forensic Data Summary

The following tables synthesize the specific data points extracted from the Paradise Papers and legal filings regarding the asset valuations and corporate network.

Table 7.1: The PetroSaudi Asset Valuation Discrepancies

| Asset | Internal Valuation (Pre-Deal) | External Valuation (Ed Morse) | Actual Outcome | Source Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serdar Oil Field (Turkmenistan) | Zero / Contingent Liability | US$2.9 Billion | License terminated; Asset swapped for debt notes. | Emails between T. Obaid & P. Mahony [4]; Termination records.[14] |

| Good Star Limited | N/A (Hidden) | US$700 Million (Loan Repayment) | Verified as Jho Low shell company. | Bearer share records in Paradise Papers.[15] |

| Venezuelan Drillships | Purchase Price (~$185m) | US$300m+ (Arbitration Award) | Funds seized by DOJ as proceeds of crime. | DOJ Forfeiture Complaint.[24] |

Table 7.2: Key Offshore Entities in the PetroSaudi Network

| Entity Name | Jurisdiction | Role in Fraud | Paradise Papers Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PetroSaudi Holdings (Cayman) Ltd | Cayman Islands | Parent Company / JV Signatory | Client of Appleby; flagged for missing KYC.[1] |

| 1MDB-PetroSaudi Ltd | BVI | Joint Venture Vehicle | Conduit for initial US$1B transfer.[5] |

| PetroSaudi Oil Services (Venezuela) Ltd | Barbados | Operational Vehicle | Holder of PDVSA contract; subject of DOJ seizure.[10] |

| Good Star Limited | Seychelles | Theft Vehicle | Recipient of diverted US$700m; Jho Low owned.[15] |

8. Conclusion: The Legacy of the Leak

The Paradise Papers provided the final, irrefutable layer of evidence necessary to deconstruct the PetroSaudi 1MDB fraud. While Xavier Justo’s 2015 leak exposed the intent of the perpetrators through their operational emails, the Paradise Papers (2017) exposed the structure of the fraud through the files of their legal architects.

The "PetroSaudi Oil data" requested by the user was, in reality, a fabrication constructed by offshore lawyers and compliant valuers.[14] The Serdar oil field in Turkmenistan was never a viable asset for PetroSaudi; it was a geopolitical dispute packaged as a multi billion dollar concession. When that narrative was exhausted, the fraud migrated to Venezuela, where the legal instruments of international arbitration were weaponized to launder the stolen funds.

The granular details from the Paradise Papers, such as the "Code Red" at Appleby, the hidden bearer shares of Good Star, and the "pay now, argue later" clauses in the Venezuelan contracts, demonstrate the sophistication of modern sovereign wealth theft. This case stands as a stark warning of how the "Sand the Wheels" of corruption can devastate a national economy, requiring a robust, technology driven response from regulators to dismantle the offshore secrecy that makes such crimes possible.[26]

Referenzen

- Paradise Papers: The Latest Offshore Leak | Insights - Jones Day

- Paradise Papers - Wikipedia

- 1Malaysia Development Berhad - Wikipedia

- Directors Rated PetroSaudi Project As Being Worth “Zero”! - Sarawak Report

- Case 2:20-cv-08466 Document 1 - Department of Justice

- PDVSA v. PetroSaudi, Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit - Jus Mundi

- Read the Paradise Papers documents - ICIJ

- The Paradise Papers - the corruption factor - Transparency International EU

- ICIJ Releases Paradise Papers Data From Appleby

- petrosaudi oil services (venezuela) ltd. - ICIJ Offshore Leaks Database

- 1MDB whistleblower under investigation in Switzerland - SWI swissinfo.ch

- Behind the 1MDB Scandal with Xavier Justo - Workiva

- Xavier André Justo's brutal account of whistleblower retaliation - EQS Integrity Line

- PetroSaudi's US$1.5 billion assets non-existent, says DAP lawmaker - Yahoo News Singapore

- Reviewing G20 promises on ending anonymous companies

- Sovereign Wealth Funds: Corruption and Other Governance Risks

- Paradise Papers: Secrets of the Global Elite - ICIJ

- Opening Up Offshore Secrecy | Transparency International UK

- OPENING UP OFFSHORE SECRECY - Transparency International UK

- VALENTINA LARES - Armando.info

- united states v. petrosaudi oil serv. - Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals

- Petrosaudi Oil Services (Venezuela) Ltd v Novo Banco S.A. & Others - 7KBW

- UNITED STATES v. << (2023) - FindLaw Caselaw

- U.S. Seeks to Recover More Than $300 Million in Additional Assets Traceable to Funds Allegedly Misappropriated from Malaysian Sovereign Wealth Fund | United States Department of Justice

- 1Malaysia Development Berhad scandal - Wikipedia

- Corruption is costing the global economy $3.6 trillion dollars every year

- Fighting Corruption should be an agenda in the upcoming 26th Asean Summit

- Corruption and Economic Growth: The Transmission Channels - Munich Personal RePEc Archive

- (PDF) Corruption and economic growth: A meta-analysis of the evidence on low-income countries and beyond - ResearchGate

- Fighting Corruption in Developing Countries to Meet the Challenge of Human Capital Development: Evidence from Sub-Saharan African Countries - NIH

- Corruption and Economic Growth: The Transmission Channels - IDEAS/RePEc

- NACP 2019-2023: MACC has completed 29 out of 115 initiatives – Azam Baki

- NATIONAL STATEMENT THE 10TH SESSION OF THE CONFERENCE OF STATE PARTIES TO THE UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUPTION 11 A - Unodc

- E-Government Development on Control Corruption: A Lesson Learned from Singapore - ResearchGate

- 2024 TI CPI: Singapore Rises 2 Spots to 3rd Least Corrupt Country in the World, Top in Asia Pacific

- Malaysian Government launches the National Anti-Corruption Strategy 2024-2028 | Skrine